Fashion Pioneer Ric Daniels Dreams of a Comeback; But First He Needs a Place to Live

By Jeffrey Anderson and Jim McElhatton. Photographs by Andy DelGiudice unless noted in caption.

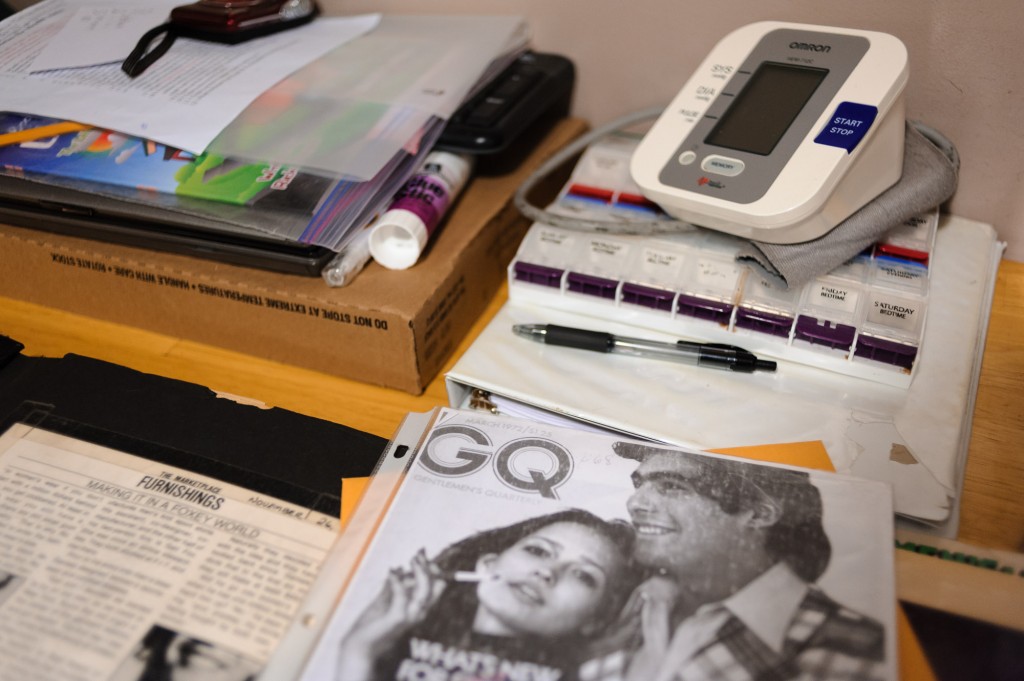

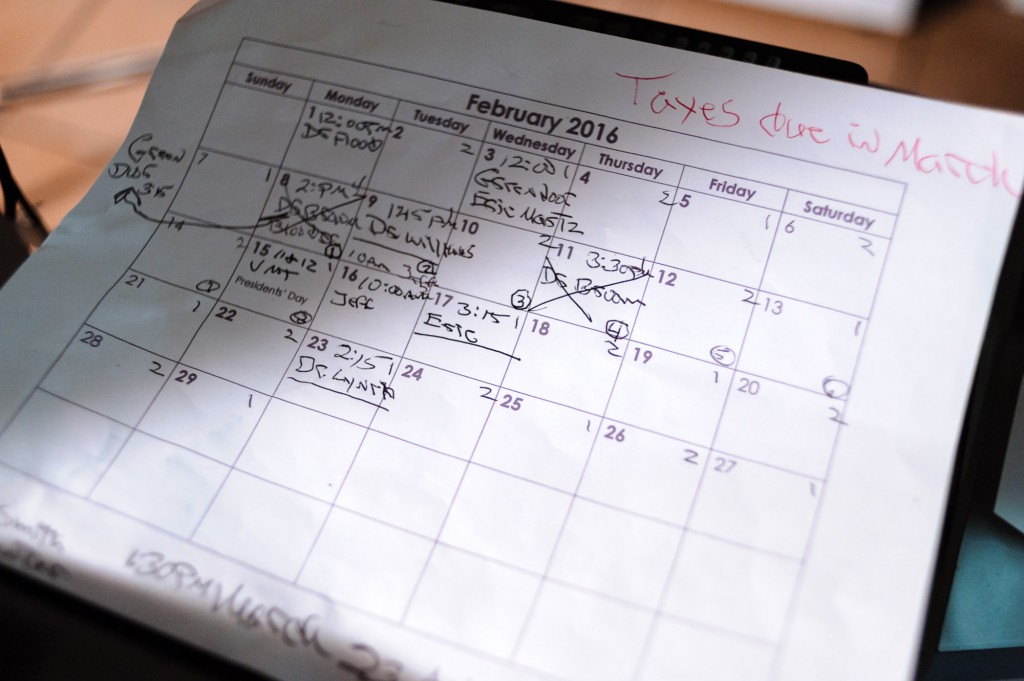

Each day, in a tiny basement apartment in Brightwood Park, Rick Daniels‘ home health aide Taka checks his blood pressure. If it’s over a certain level, he goes to the hospital, and if necessary, a nurse draws up to 650 milliliters of blood at a time. “I had it down to once a month with medications, but they’re terrible,” he says of side effects such as headaches and triple vision.

In addition to Polycythemia Vera, the bone marrow cancer that causes his blood pressure to spike, Rick, at age 65, takes medication for Crohn’s Disease, Colitis, Osteoporosis, Depression, Bipolar Disorder, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and a prostate condition.

Lately, however, he has a more pressing concern: He cannot get by on a $1,029 a month Social Security check that after rent leaves him with $229 to eat, pay bills and fend off creditors, including Medicaid, due to a clerical error by his home health provider. “I owe everybody in town,” says Rick, reflecting on his ruined credit, and his fear of eviction.

Rick’s apartment is low-ceilinged and cluttered, about 600 square-feet; just steps from a kitchenette, stuffed animals are arranged on the backrest of a sofa, and cardboard boxes serve as tables. A converted garage in the rear houses exercise equipment that he rarely uses. On cold winter days he turns on the oven and leaves the door open.

Rick’s apartment is low-ceilinged and cluttered, about 600 square-feet; just steps from a kitchenette, stuffed animals are arranged on the backrest of a sofa, and cardboard boxes serve as tables. A converted garage in the rear houses exercise equipment that he rarely uses. On cold winter days he turns on the oven and leaves the door open.

Living as he does in a residential neighborhood with drug activity too close for comfort, Rick keeps his front window and door covered with cardboard. He rarely ventures out after dark, and sleeps on an air mattress, haunted by his own fate, and frequent gunfire.

“They’ve been there for over a month,” he says of two police vans and flood lights at the end of his block. “After they leave it’ll stay quiet for a bit. Then somebody else will get shot and they’ll bring them back.”

Rick has few friends, though he speaks placidly about his stuffed animals and the birds and squirrels he feeds from just outside his door, all of which have names. Most days, he watches classic movies with Taka, who is there with him 12 hours a day, five days a week; or he sits at his computer researching affordable housing options. He knows that if he is evicted, he is destined for a men’s shelter, where he’ll no longer have in-home health assistance. It’s a terrifying prospect, but Rick keeps a positive outlook. “She was sent from heaven,” he says fondly of Taka.

One night in January, Rick heads to the Embassy Suites Hotel in Tenleytown, to an Advisory Neighborhood Commission meeting, looking for housing assistance. Inside ballroom No. 1, he moves toward the front of the room of about 100 attendees, raises his hand, and keeps it raised, for as long as it takes to get the attention of Mayor Muriel Bowser, who happens to be attending the Ward 3 neighborhood meeting.

Bowser’s appearance, even though not in Ward 4, where she and Rick both live, is timely. Rick reached out to the D.C. Council for help a few months ago. He recalls a staffer of Bowser’s protege, Ward 4 Council Member Brandon Todd, telling him to go look for an apartment on Craigslist. (Todd’s office ignored repeated requests for comment. When District Dig visited his office, Todd said he would have a staffer contact Rick that day. According to Rick, Todd’s office has never called him.)

Now, stinging from that deflection, he is encouraged that the mayor is talking about ending homelessness by 2020, and about the funds she is putting toward low-income housing.

When Bowser calls on him, Rick is ready: “I get up and say, ‘I’m going to a shelter tonight.’ I didn’t want to put her on the spot but I had to do that.” Though he has more to say, about the drug-dealing in his neighborhood and his health condition, he keeps it to his tenuous living situation, and leaves the meeting with a stack of D.C. government business cards and a vague promise from Bowser that her staff will be in touch. “Her response was ‘so-and-so is here from my office,’” Rick says.

A few days later, he gets that call from the mayor’s office. A staffer directs him to housing options similar to what he has already identified and cannot afford — nothing sustainable. He feels like he’s running out of options, and time. “They recognize my situation, but they haven’t done nothing,” he says, later in the month. (The Dig contacted Bowser’s office and a number of her agency representatives and has yet to receive comment.)

Though Rick is on the verge of falling through the cracks, seemingly a random individual without much of a past or future, he actually once led a life that a middle-class child from D.C. could only dream about. And despite his current predicament, he still holds on to the hope of replicating his unlikely triumphs.

Barry Ricardo Daniels was born in 1950 and raised on California Street in Adams Morgan, where he did not have what most would consider a healthy childhood. “It was a nice apartment, but it had holes in the wall, and I used to eat the plaster,” says Rick, who is tall and slender, all of 163 pounds, and possessed of a gentle voice and demeanor. “I don’t know how the holes got there, but the plaster tasted good to me, so I ate it,” he says.

One day, Rick went to the hospital with a case of lead poisoning. From there on, he says, his brain failed him in significant ways. He experienced learning difficulties in the 3rd grade, and was held back in the 4th and 6th grades. By the 7th grade, he was barely reading at an elementary school level. “I got bullied because I couldn’t read or write so well,” he says.

Rick compensated by being a sharp dresser and throwing good parties, which kept the bullies off his back. He shopped at the Cavalier Men’s Shop at 10th and F, became popular with girls, and began to explore his creative side, and fashion. He was still trying to get through 10th grade when he turned 18 and got expelled from Coolidge High School. “The principal said I was wasting their time,” he recalls.

With an interest in clothes and design, Rick moved to New York City and enrolled at the Fashion Institute of Technology. He already knew how to sew, and soon he mastered the patterns and simple designs for carefully chosen fabrics he would turn into men’s shirts. With his then-wife, Gail Fox, who he met at FIT, and one sewing machine, Rick launched Foxey World Shirts in 1968, in a loft apartment at 147 W. 40th Street, in the heart of the New York’s Garment District.

To get his shirts placed in department stores, Rick says he would visit the sales manager, and if the manager even grudgingly agreed to put, say, a half dozen shirts on display, Rick would have five friends visit the store and scoop them up. With one shirt left on the shelf, he’d then have Gail and her friend come in and fight over the last sale. The ruse worked with Bloomingdale’s, which eventually ordered shirts for all of their stores. Macy’s, Gimbels and Abraham & Straus, among other department stores in other cities, followed suit.

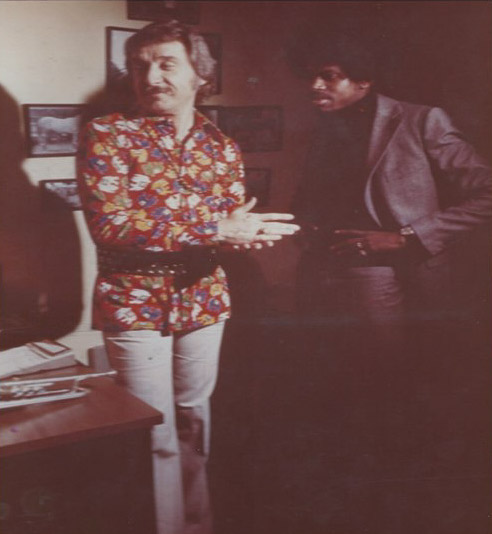

Doc Severinsen of The Tonight Show in a Foxey World shirt. Foxey World Archives

He took a more direct approach to crack into the celebrity market. Rick would go to a concert and find his way backstage, where he would approach an assistant or handler, and give them a shirt that he had designed with the performer in mind. The assistant would usually return in a matter of minutes, and usher Rick in to speak directly with the artist. His tactic worked with the Delfonics, his first big-name customers. And it worked with Jimi Hendrix, Nick Ashford and Isaac Hayes, who asked him to make a jumpsuit. He met Muppets creator Jim Henson at a party — Henson wanted a Foxey World shirt — and he was happy to oblige when Tonight Show bandleader Doc Severinsen took a liking to Foxey World shirts as well.

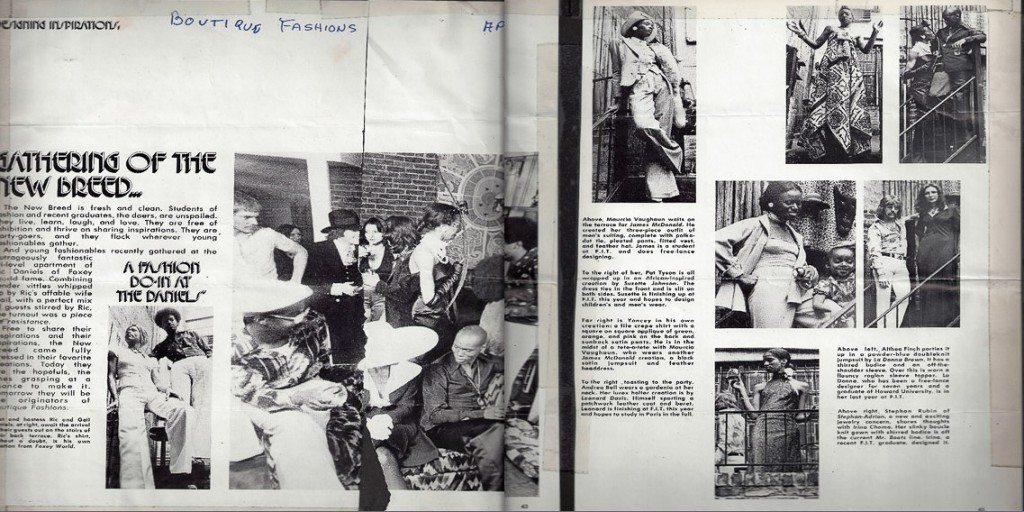

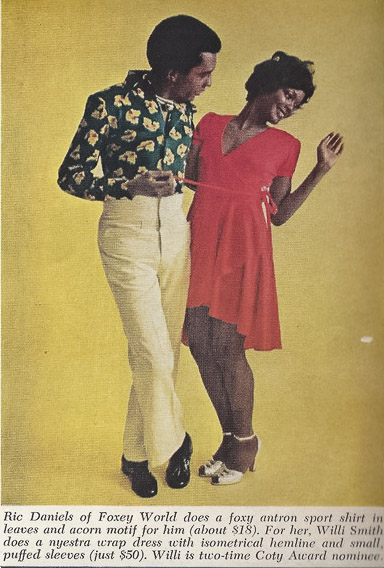

Ebony Magazine, February 1974. Foxey World Archives

With department store accounts and a high-end clientele, the company grew to 75 workers at an off-site factory in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Rick, who began to go by “Ric,” and his wife, were young and rich.

Sitting at his computer one day in February, Rick leafs through photographs of celebrities wearing his shirts, and magazine and newspaper clips from Ebony, Essence, GQ, New York Times Magazine and The Washington Post. One photo shows Calvin Klein during a party at Rick’s apartment hosted by Vanity Fair.

“I was a star, with nice cars, front row seats to concerts, the subject of many articles,” he says. “I felt pretty good about myself, for a kid who couldn’t read or write. That was when my creativity was at its best. I hope to get back to it someday.”

Rick had an exciting run, from 1968 to 1974, but mass production and cheap knockoffs caused business to dry up, and he was forced to shut down Foxey World. GQ offered him a fashion editor job, he says, but when he struggled to fill out the human resources paperwork, they knew something was wrong. “How was I gonna be an editor if I couldn’t read or write?” he says. Bloomingdale’s offered him a sales job, as a first step to becoming a buyer, but when he took longer than he should have to fill out sales and inventory reports, that job didn’t last long, either.

The reversal of fortune was tough, Rick says. With his fashion career behind him, and an inability to compete for jobs that required literacy, he moved to Boston and went to work as a temp for Avis Car Rental as a shuttler. “Didn’t take long for them to realize that I have good customer service skills,” he says, without any discernible pride. He cycled through various functions with the company and made himself valuable any way he could.

Rick’s career with Avis took him to Minneapolis, back to D.C., to Norfolk, Virginia, and then back again to D.C. In 2007, he was diagnosed with Polycythemia Vera, and moved in with his aging mother up on Third Street, N.W., near Butternut. His mother died four years later. Rick says a family dispute led his siblings to sell his mother’s house out from under him. In a pair of complaints in D.C. Superior Court, he alleged that his siblings also bullied him, and threatened to hurt him or sabotage his Medicaid. (He dismissed both cases.)

Being subjected to bullying is a recurring theme in Rick’s life. His learning disability and gentle nature have at times made him appear vulnerable. But just as he turned to fashion to compensate for a reading and writing deficiency, he turned to a new creative pursuit to cope with his health problems, and the regimen of medications that fill an entire 8 x 10 inch piece of paper. Not to mention the blood draws as voluminous as a large soda cup.

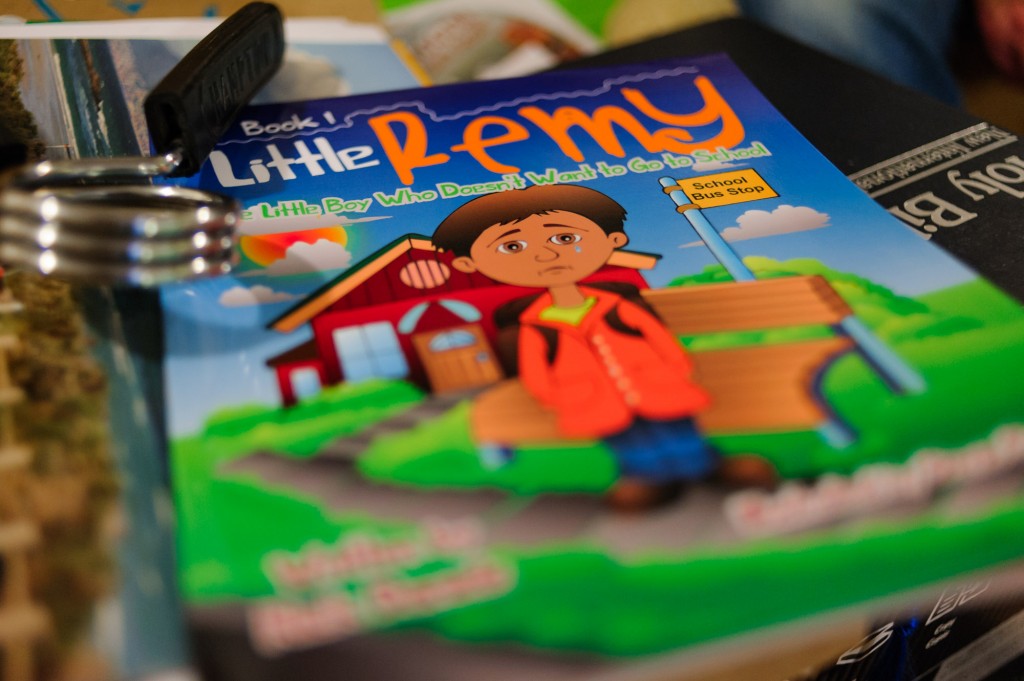

Little Remy is about a fictional boy who, like Rick as a child, has been bullied and does not want to go to school. Rick conceived Little Remy in June 2012, and as is his entrepreneurial nature, revived the Foxey World brand so he could self-publish the books. He was encouraged when retail giant Barnes & Noble agreed to stock them. He says he even gave a copy to Mayor Bowser when she was his councilmember. “I had hoped to hear something from her,” he says, wishing aloud that someone would show interest in a local, self-published book about an issue that affects troubled kids.

Colorfully illustrated, with a simple message, Little Remy depicts a boy who overcomes his fears and learns to cope with bullying. But there is something peculiar about the book’s main character: Little Remy has straight hair and a light complexion. On a visit to Rick’s apartment one day this winter, The Dig asks Rick why Little Remy isn’t black, like him. He says an earlier version of Little Remy was a black child, but a retailer told him he had to lighten the boy’s skin for it to appeal to a national audience.

Sales through Barnes & Noble have been slow, and Rick is not even sure they display his books anymore. “The only sales are the ones I sell myself,” he says. “It’s just like Foxey World shirts: Nobody knows about Little Remy, so it’s a struggle. If I was Steve Harvey, or Ellen DeGeneres, or Joel Osteen, that wouldn’t be a problem.” The Dig asks Rick if he has resorted to his sales techniques of back in the day, and he replies, “The local system has disappointed me so much. I can’t handle any more disappointment right now.”

Little Remy is not the only reflection of Rick’s life. One day a raggedly stuffed tiger cub falls off the back of the sofa, and Rick shares its backstory. He says he found it abandoned on the sidewalk one day. He brought it home and gave it a name, then composed a children’s book he has yet to publish: Lucky Finds A Home.

February is rough. The accumulation from Snowmageddon blows down into Rick’s stairwell and up against his door, rising to four feet, making it impossible for him to leave until his neighbors shovel him out. He continues to inquire at city agencies and nonprofit organizations about a sustainable housing option, but the prospects seem dim.

Although there are many options for seniors with physical and behavioral health issues, it helps to have guidance in navigating the system. Even then, the process can seem interminable. Rick’s been on a waiting list for public housing assistance, which would reduce his rent to 30 percent of his monthly Social Security check, since 2009. “Hasn’t moved an inch,” he says one day, with a rare edge to his voice. He’s also been on a list through the Department of Behavioral Health, but again, he’s just one of many. “I heard one way is to go to a shelter,” he says warily. “If I wasn’t paying rent (and staying at a shelter) I could store my things until something opened up.” The problem with that scenario, Rick says, is he would lose his Medicaid and his home health aide, which require a permanent address. “I don’t even want to think about it,” he says.

Jonathan McHugh, an advisory neighborhood commissioner in Ward 3 who was at the fruitless meeting Rick attended in January, says Bowser is putting an emphasis on affordable housing that he hasn’t seen before. “She at least pays lip service to it,” he says. “What is needed is a longterm, durable solution.”

McHugh recognizes that Rick is “close to the line” of homelessness, and says that once he crosses that line, it’s hard to get out. “Craigslist is not gonna work for someone his age,” says McHugh. “It would be better for us as a city that [Rick] doesn’t fall into that hole.” So McHugh took it upon himself to help Rick out, with a call to Chuck Thornton, marketing director at Seabury at Friendship Terrace, an affordable senior living community near where Rick grew up.

The units at Friendship Terrace have floor-to-ceiling windows and an evening meal, for $1,139 per month. Rick would be eligible for a Section 8 housing voucher that would reduce his rent to $299 a month — once one of a limited number of vouchers becomes available. Thornton indeed contacted Rick, but informed him that he’d be the young kid on the block, and that it could take up to three years for a voucher to become available.

Looking back on the January meeting, McHugh recognizes that the city could do a better job connecting people in Rick’s shoes not just to housing but to vital social services. “There were so many agency reps there, it would be great if one of them said, ‘Hey, that’s what we do.'”

By the end of February, Rick is stressing out to the point of sleeplessness. One day he lets on that he had a close call in his neighborhood. “I was on my way to church, which is right down the street,” says Rick. “I was dressed up, had a fedora and a cashmere overcoat on, and the next thing I knew I was laying on the ground, with people from the church helping me up.”

By Rick’s estimate, he had been on the ground, in the street, for close to an hour. Just fell down and went fast asleep on the ground, until someone found him. “Maybe it’s narcolepsy,” he offers. “I’ve been having nightmares, barely sleeping at all.”

A week or so later, Rick has more bad news: His upstairs landlord has informed him she is raising the rent to $1,000. “I can’t blame her, rents are going way up in this town,” he says, without a hint of bitterness. “But I can’t live on $29 a month.”

One day in early March, Rick’s home health aide sits down with The Dig and talks about what’s been going on with her client. “He’s very stressed,” says Taka, a reserved, 28-year-old D.C. native. “He tries to keep a sense of humor and be optimistic, but the stress is written on his face.” Just last week, Taka says, Rick had to go to Georgetown Hospital for a blood draw. “A big bag,” she says. “I don’t think he barely sleeps, or at least he doesn’t get consistent sleep. He’ll have his moments when he’s down, then he’ll snap out of it and say, ‘I’m gonna keep pushing.’ He inspires me in a lot of ways.”

Conversely, Rick has come to rely on Taka for more than home health services. Besides taking him to the hospital when needed, she drives him to social services agencies and to scout out housing options. Together they reach out to Green Door Behavioral Health, a non-profit agency that delivers community-based care to individuals with behavioral health and chronic physical conditions. “They’re not the friendliest people but they’re close by,” Rick says of Green Door, indicating that he has not found the agency to be helpful in navigating D.C.’s byzantine housing programs.

“I can be a witness, Green Door has not done a great job,” Taka says. “He’s taken it on himself to do the job that the program is supposed to do. If you aren’t proactive you could be clean out of luck.”

A couple more weeks pass, and Rick emerges with some encouraging news: Giant Food has agreed to let him sell Little Remy out in front of several stores, four hours at a time. “Gotta compete with the Girl Scouts,” he jokes. Days later, The Dig goes up to Columbia Heights and there, standing in the blazing sun, with a table set up behind him, is Rick, hustling books in front of the Giant, just off 14th Street.

Rick is a sight, standing there under an azure sky with puffball clouds, sporting a blue Coogi ball cap, T-shirt of the same color and Coogi jeans, with embroidered back pockets. “Please support Little Remy,” he says to passersby, who can’t resist his soft sales pitch.

Something else is different about Rick on this early spring day. He looks vital, focused; it’s a clear contrast to how he appeared just a month ago, in his ’round-the-house clothes, during the bleak days of winter, in a below-ground apartment, wondering and worrying about what may come. A woman pushing a baby stroller, with her toddler and teenage son in tow, stop to talk. The son, to The Dig‘s amazement, is named Remy. Naturally, they buy a book.

Rick takes a break and comes over to talk. He has an even bigger development to report: Not one but two housing options have opened up! “I got so many apartments I don’t know what to do,” he says in his typically reserved manner.

One is an apartment at North Capitol Commons, which is still being built, he says. Another one is in a senior building, a Section 8 unit he applied for last year that would reduce his rent by 70 percent, called The View at Edgewood Terrace, near Rhode Island Avenue and Fourth Street N.E. “It was a six-month wait, but that was pretty short,” he says.

Taka is standing nearby, chatting with other passersby, keeping one eye on Rick as she explains to potential customers what he is doing there, what he has been going through. She acknowledges that circumstances had been dire. “If he loses his place, he loses a lot of things,” she says. “It’s a domino effect.”

She too has has noticed a change in Rick lately, Taka says, noting that he has thrown himself into the maze of social and housing services that vexes so many of the city’s most vulnerable citizens. The key, she says, has been his perseverance, his refusal to get lost in the system. Getting Giant to agree to let him sell his books has been a boost as well. “He’s been selling out of books a lot lately,” she says. “It’s hard out here, but sometimes it does work out. I told him, ‘you’re lucky.'”

Rick knows it. And he’s ready, ready for some security, some peace of mind, as he prepares to make a comeback, this time as a children’s book publisher. Lucky, indeed. Just like the stuffed animal he took in. But Rick has even bigger plans for himself. He says he is rejuvenated by being out in public, meeting people, telling his story. “This is all practice for when I go on Oprah, and Ellen, and Joel Osteen,” he says.

Out here on the street, watching Rick soak up the attention, there is not a single doubt that he believes it, too.

Epilogue: The Dig has learned that Rick is set to move in to a Section 8 unit at The View at Edgewood Terrace on May 1. And book sales are steady; Little Remy is getting more attention than ever before.